InvasiveSpecies

Invasive Species

An invasive species is a non-native species introduced to an area that has an adverse economic, ecologic, or environmental effect on the native ecosystem.[1]

Invasive species spread and excel in the ecosystems they invade due to a lack of competition or a lack of predation from native organisms. In the context of coral reefs, invasive species frequently refers to the lionfish, which is native to the Pacific and is currently invading the Caribbean Sea and Atlantic due to its voracious appetite and lack of natural predators.[2]

Impact

There are a plethora of community-wide impacts that occur when non-native species are introduced to a certain area. For example, the introduction of one invasive species can often facilitate the invasion of a second invasive species by altering the overall structure of the ecosystem [3]. Although many types of organisms or plants will not directly affect the trophic structure of the ecosystem, they will cause some sort of ecological shift in the previously homeostatic ecosystem. For example, one study noted that the invasion of a type of algae did not cause a direct shift in the trophic structure of the ecosystem, but rather inhibited the growth of a native kelp forest which was subsequently overrun by the non-native species[3].

Common examples

Lionfish

Lionfish are any fish of the genus Pterois. They are venomous predatory fish native to the Indo-Pacific region. Two species, Pterois miles and Pterois volitans have established themselves as a significant invasive species in the Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico, and Atlantic Ocean. Lionfish are popular aquarium fish due to their bright warning coloration.

Sightings and Dispersal

Lionfish were most likely introduced into the Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico, and Atlantic Ocean by aquarists. The most popular theory is that six lionfish were released accidentally into Biscayne Bay due to the destruction of a beachside aquarium by Hurricane Andrew, though this claim has since been refuted by one of the initial reporters.[4] The current population of lionfish in these areas are likely the descendants of lionfish released by aquarists, either accidentally or intentionally. [4]

Another theory for the appearance of Lionfish in the Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico, and Atlantic Ocean is that at some point in their lifecycle, lionfish were taken into the ballast tanks of ships traversing the Panama Canal from the Pacific side and released in the Atlantic. This theory is generally not given much credence by respected experts.

Appearance and Distribution

Lionfish are commonly found from Florida to Cape Hatteras along the East Coast of the United States. They are widespread in the Bahamas, Bermuda, and the Greater Antilles, and the Western Caribbean coasts of Mexico, Belize and Honduras. Sightings have been reported as far south as Colombia, Aruba, and Panama, and as far north as Rhode Island.[5][6]

Lionfish can not only be found in a wide geographic range, but they can also be found throughout the water column. A recent study found significant populations of large lionfish at a depth of 300 feet. [7]

Another recent study conducted off the coast of North Carolina found the highest densities of lionfish from 38 to 46 meters deep and in locations with a winter mean water temperature of 15.3°C and higher. [8] In the winter in North Carolina, where the Gulf Stream plays a large role in water temperatures, deeper water is significantly warmer than the surface water. Whitfield's research suggests that average water temperatures plays a crucial role in the distribution of lionfish, and "increasing temperatures could favor a potential expansion of invasive lionfish and native tropical species into the nearshore waters on the North Carolina shelf, resulting in unforeseen community structure and trophic disruptions." [8]

Impact on Coral Reef Ecosystems

There are a variety of mechanisms in which the lionfish invasion can alter a coral reef ecosystem. One proposed mechanism is through the predation of native herbivores. Because the lionfish have such a voracious appetite, they have the potential to wipe out all of the grazers in a coral reef ecosystem. [2] Once all of the grazers have been predated, the ecosystem is extremely vulnerable to overwhelming algal blooms.

Overrunning algae can potentially harm the coral reef by preventing sunlight and nutrients from reaching the coral, thus breaking down the symbiotic relationship between the coral and zooxanthellae. This could lead to extensive coral bleaching[9].

Effects on Fisheries

The Lionfish invasion has the potential to greatly affect coral reef fisheries. Lionfish are relatively large and have no natural predators, and they can eat astounding numbers of smaller fish that already inhabit coral reef systems. [2] Coral reefs are already experiencing an abundance of pressure on their trophic organization due to fishing pressure. [4] As such, the lionfish invasion can only serve to compound that pressure on the coral reef ecosystem.

Furthermore, the lionfish invasion subsequently harms the fishery because the fishermen cannot catch the same mass of fish as they previously were. [9] The fishermen may even resort to fishing down the food web|fishing down the food web, which could prove detrimental to the entire ecosystem and fishery.

Control and Management

Because experts consider any attempts to reverse the invasion to be futile, efforts are now being concentrated on controlling the lionfish population. Several methods of control have been suggested, including encouraging revitalization of local predator species, limiting lionfish trade among aquarists, encouraging lionfish fishing and consumption amongst humans, and killing easily spotted specimens.[4]

One way to control the lionfish population in the Caribbean would be to maintain a healthy population of species that prey upon the lionfish, including large groupers, sharks, and other species that feed on lionfish eggs and juveniles. Divers in Palau have noted that locations with large concentrations of large and medium sized groupers often have fewer lionfish.[4] Protecting Caribbean grouper and shark populations might lead to an increased number of predators of lionfish, limiting the population. Another method of limiting lionfish population explosion is reducing the fishery pressure on species that occupy the same ecological niche as the lionfish.

However, new research from UNC-Chapel Hill suggests that an increase in larger predators (sharks, groupers, snappers, etc.) does not correlate with a lower number of lionfish.

"The team surveyed 71 reefs, in three different regions of the Caribbean, over three years. Their results indicate there is no relationship between the density of lionfish and that of native predators, suggesting that, 'interactions with native predators do not influence' the number of lionfish in those areas, the study said.

The researchers did find that lionfish populations were lower in protected reefs, attributing that to targeted removal by reef managers, rather than consumption by large fishes in the protected areas. Hackerott noted that during 2013 reef surveys, there appeared to be fewer lionfish on popular dive sites in Belize, where divers and reef managers remove lionfish daily.

The researchers support restoration of large-reef predators as a way to achieve better balance and biodiversity, but they are not optimistic that this would affect the burgeoning lionfish population." [10]

Another proposed method of controlling the population explosion is encouraging fishing of lionfish. While divers and spearfishermen are already encouraged to kill all lionfish that are easily spotted and captured, steps could be made to educate people on the culinary uses of lionfish. If lionfish was made a staple of Caribbean and Atlantic diets, fishing pressure would surely limit the population explosion.

Unfortunately, though, lionfish have recently been added to the US FDA's Fish and Fishery Products Hazards and Controls Guidance, also known as The Guide, for a list of the fish that may carry dangerous levels of ciguatoxins. [11] Nevertheless, Whole Foods has recently indicated that it will begin selling lionfish at its stores in Florida. [12]

Algae

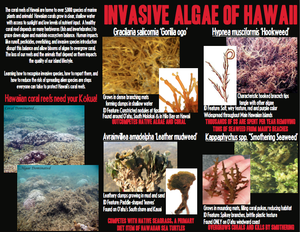

There are a variety of invasive algae that inhabit Caribbean coral reefs. They include Graciliara salicornia, Hypnea musciformis, Avrainvillea amadelpha, and Kappaphychus spp. [9].

Amphipods

Some amphipod inhabitants of coral reefs are also invasive [13].

The Ericthonius braziliensis is an amphipod that has been introduced to the Caribbean by attaching themselves to ship hulls that enter and exit the Caribbean. Stenothoe valida is a small amphipod that was likely introduced to the Caribbean via ship ballast water. This amphipod has yet to largely impact the coral reef systems, but it's populations should be monitored and controlled to prevent future impacts.

Sponges

There are also some non-native varieties of sea sponges that inhabit coral reef systems [13]. The Mycale cf. cecilia is a sponge that hitchhiked its way into the Caribbean on the bottom of ships' hulls.

Management Plans

One example of an invasive species management plan is the Aquatic Invasive Species Project in the Hawaiian Islands. [9] Its goals include:

- Coordination and collaboration between agencies

- Prevention

- Monitoring and early detection

- Response, eradication, and control

- Education and outreach

- Research

- Policy

Another management system is the Seychelles Invasive Species Project.[13] It is an ongoing project with the primary objectives of:

- Enhancing the capability of staff and institutions involved in monitoring

- Improving awareness of local communities to the threats posed by these introduced organisms and their economical impacts

Additional Resources

Media:ENEC Presentation.pdf - Powerpoint presentation

Media:Ballast_Water.pdf - Ballast Water handout

References

- ↑ http://www.oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/invasive.html

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Morris, James A. and John L. Akins. "Feeding ecology of invasive lionfish (Pterois volitans) in the Bahamian archipelago." Environ Biol Fish. Vol. 86: 389:398. 2009

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Levin et al. "Community-wide effects of non-indigenous species on temperate rocky reefs." Ecology. Vol. 83: 3182:3193, 2002

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 http://coris.noaa.gov/exchanges/lionfish/

- ↑ Albins, Mark A. and Mark A. Hixon. "Invasive Indo-Pacific lionfish Pterois volitans reduce recruitment of Atlantic coral-reef fishes." Mar Ecol Prog Ser. Vol. 367: 233-238. 2008

- ↑ Barbour et al. "Mangrove use by the invasive lionfish Pterois volitans." Mar Ecol Prog Ser. Vol. 401: 291-294. 2010

- ↑ http://oregonstate.edu/ua/ncs/archives/2013/jul/lionfish-expedition-down-deep-are-where-big-scary-ones-live

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Whitfield PE, Muñoz RC, Buckel CA, Degan BP, Freshwater DW, Hare JA (2014) Native fish community structure and Indo-Pacific lionfish Pterois volitans densities along a depth-temperature gradient in Onslow Bay, North Carolina, USA. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 509:241-254.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 http://www.hawaiicoralreefstrategy.com/index.php/local-action-strategies/aquatic-invasive-species

- ↑ http://college.unc.edu/2013/07/12/lionfish/

- ↑ http://www.foodsafetynews.com/2013/03/fda-adds-lionfish-to-list-of-fish-that-may-carry-ciguatoxins/#.U5c-GZRqwt0

- ↑ http://money.cnn.com/2016/05/27/news/companies/whole-foods-lionfish-invasive-species/index.html

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 http://www.iucn.org/about/work/programmes/marine/marine_our_work/marine_invasives/seychelles/