Bleaching

From coraldigest

Coral Bleaching

What is bleaching?

Simply, it is the release of coral symbiotic zooxanthellae . A more in depth definition is the loss of all or some symbiotic algae and photosynthetic pigments by the coral animal resulting in their white calcium carbonate skeleton becoming visible through the now translucent tissue layer making them appear white or ‘bleached’ of their original color [1] [2]

- Corals and symbiotic relationship

- What are zooxanthellae? - Dinoflagellates that live in coral tissues

- What they do/importance? – photosynthesis, CO2 removal

- Expulsion of zooxanthellae – give corals color, they now appear white

Causes

- SST

- Stress on corals

- Affects on symbiotic relationship

- Past, present, and future predictions/ frequency of bleaching events [3]

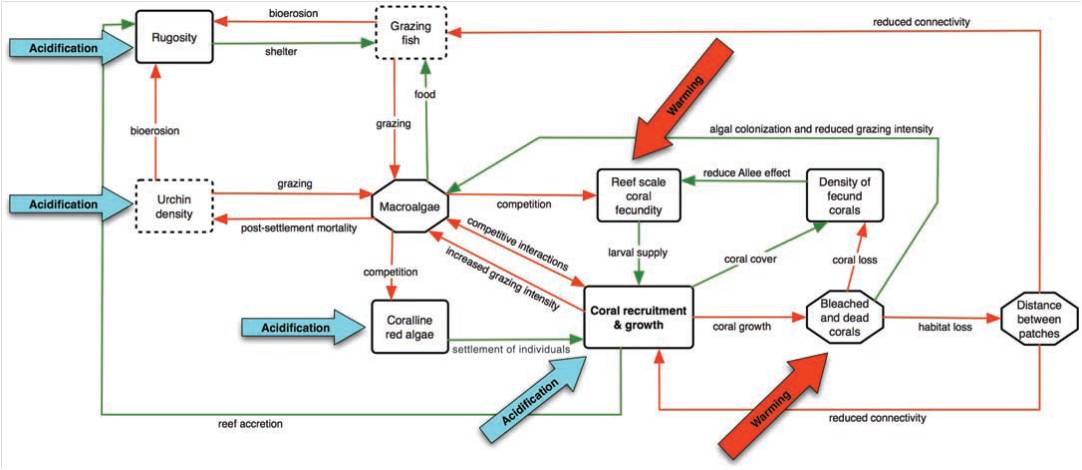

- Acidification [4]

- What is acidification? – CO2 dissolves in ocean and increases acidity which dissolves CaCO3

- Impact of acidification on bleaching – increases bleaching events

- Synergy with SST – higher SST amplifies acidification effects and bleaching

- Stress

- Types

- Elevated temperature

- High solar irradiance

- Disease

- Hostile/changing environment

- Disruption of symbiotic relationship

- Why expel zooxanthellae?

- Types

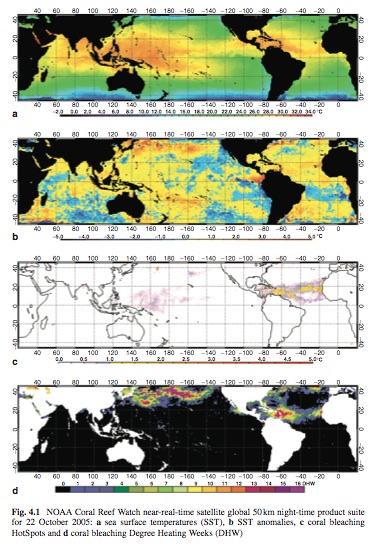

NOAA Coral Reef Watch near- real-time satellite from 2205 showing a.SST b.SST anomalies c.coral bleaching HotSpots d. coral bleaching Degree Heating Weeks[1]

NOAA Coral Reef Watch near- real-time satellite from 2205 showing a.SST b.SST anomalies c.coral bleaching HotSpots d. coral bleaching Degree Heating Weeks[1]

Effects

- Disease – frequency increases

- Ecosystem/reef effects

- Corals – productivity, recruitment, survivability/adaptation

- Fish/Other organisms – habitat, recruitment, abundance

Special Case Study

- US Virgin Islands: Bleaching 2005

- In the summer of 2005, unusually calm seas and record setting warm seawater temperatures induced the most devastating coral bleaching ever recorded in the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI) with coral cover being more than 90% bleached and stretching from the surface to 20 meters deep. [6]

- This weather shock was followed by a breakout of disease on the reefs, which led to increase monitoring, but more partial or total coral death in the USVI.

- Two corals that create much of the framework of reefs in USVI were heavily affected: Acropora palmata and Montastraea annularis.[6]

- Montastraea annularis, while remaining very present on the reefs, dropped from 55.6 percent to 40.9 percent of coral cover over the 2 years following the bleaching event

- Acropora palmate was less affected by disease, but 50% of the corals being watched in 2005 showed signs of bleaching, marking the first record of A, palmate bleaching in the USVI.

- Researchers showed a correlation between temperature and disease, but only with the 2005 massive bleaching event. They found the size of white syndrome lesions, like white pox, increased as temperature increased for bleached colonies, but not other healthy colonies. [6]

- Even with cooler temperatures, the coral cover continued to decline, with the mean coral cover decreasing 61 percent through 2007. At peak disease after bleaching, “the mean number of lesions increase 51-fold and the mean area killed by disease increase 30 fold” in reference to levels prior to the bleaching event. [6]

- This is the only study to show such extreme declines in coral cover from disease covering such a large area. [6]

- Sunscreen and reefs

- It has been proven that sunscreen and other personal care cosmetics are potentially harmful to marine environments in terms of bioaccumulation of UV filters in animals and photodegradtion, which turns sunscreen agents into toxic by-products. They can be so harmful that they have been banned in certain high tourists areas, but there had been no studies on the effect on reefs

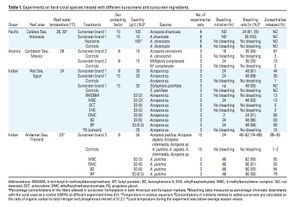

- In a study headed by faculty at Polytechnic University of the Marche, Ancona, Italy, researchers measured the effect of sunscreen on reefs from 2003-2007.

- A team conducted experiments adding aliquots of sunscreens and other common ultraviolet filters contained in sunscreen to the coral branches from several different tropical areas covering the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Ocean plus the Red Sea. Then, they observed the zooxanthellae for viral infection. [7]

- Through these experiments on site and in the laboratory, it was determined that sunscreens cause complete and rapid bleaching of hard corals, even at extremely low concentrations. This negative effect is the result of organic ultraviolet filters, which cause zooxanthellae with infections to enter a lytic viral cycle. By fostering this viral infection, sunscreens could play a influential role in coral bleaching in areas exposed to high levels of human recreation. [7]

- It was calculated that 10% of the reefs in the world could be threatened by sunscreen induced bleaching. This calculation is a result of the estimations that in tropical countries somewhere between 16,000 and 25,000 tons of sunscreens will be applied, and of that amount at least 25% will be washed off in the ocean. This leads to a potential release of 4,000–6,000 tons/year of sunscreen in reef areas. This number will only increase as humans continue to increase our use of the reefs. [7]

An example of bleached coral due to the effects of sunscreen. [7]

An example of bleached coral due to the effects of sunscreen. [7]

A data table showing the results of the experiments on various hard corals with sunscreens and sunscreen ingredients [7]

A data table showing the results of the experiments on various hard corals with sunscreens and sunscreen ingredients [7]

What we are currently doing to sustain coral ecosystems

- USGS “Science Based Strategies” example

- Coral reefs are necessary in supporting many different ecosystems

- Although threats are known, there are still strides that need to be made in how scientists respond to them and how we treat and/or prevent the current problems and threats such as carbon sequestration, ocean temp, ocean acidification, sea level rise, atmospheric dust, land-derived impacts, pathogens and disease, overfishing and ecological integrity [8]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 H. van Oppen, M. J., & Lough, J. M. (2009). Coral bleaching: Patterns, processes, causes and consequences. (Vol. 205). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. Retrieved from http://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-540-69775-6/page/1

- ↑ T. Tyrrell (2007). Calcium Carbonate Cycling in Future Oceans and its Influence on Future Climates.

- ↑ Hoegh-Guldberg, Ove (1999) . Climate change, coral bleaching and the future of the world's coral reefs. Marine and Freshwater Research 50 , 839–866.

- ↑ K.R.N. Anthony, et al. (2008). Ocean acidification causes bleaching loss in coral reef builders. PNAS vol. 105 no. 45.

- ↑ O. Hoegh-Guldberg, et al. (2007). Coral Reefs Under Rapid Climate Change and Ocean Acidification. Science 318, 1737.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 USGS. (2008, June). Coral diseases following massive bleaching in 2005 cause 60 percent decline in coral cover and mortality of the threatened species, acropora palmata, on reefs in the u.s. virgin islands. Retrieved from http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2008/3058/pdf/fs2008-3058.pdf

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Danovaro, R., Bongiorni,, L., Corinaldesi, C., Giovannelli, D., Pusceddu, A., Damiani, E., Astolfi, P., & Greci, L. (2008). Sunscreens cause coral bleaching by promoting viral infections. Environmental Health Perspectives, 116(4), 441-447.

- ↑ USGS. (2008, September). Science-based strategies for sustaining coral ecosystems. Retrieved from http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2009/3089/pdf/brewercoralfs3.pdf