CoralGeography: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

The Indo-Pacific is the largest of the three regions, encompassing the central and south pacific ocean from Hawaii and Japan down to Australia through the Indian Ocean to the east coast of Africa. All stages of fringing reefs, barrier reefs, and atolls are exhibited, but barrier reefs and atolls are the most common. Reef formations are composed mostly of hard corals and often develop prominent algal ridges on the seaward margin of the reef crest. On the shore side of the reef crest, an extensive reef flat may form. Of the three regions, the Indo-Pacific is the most biodiverse. It is home to 700 coral species and over 3,000 coral reef fishes. This biodiversity may be due to the size of the region and the abundance of coastline suitable for coral reef growth or the relatively mild effects of the Pleistocene ice age which wiped out many species from the Caribbean seas.<ref name="william" /> | The Indo-Pacific is the largest of the three regions, encompassing the central and south pacific ocean from Hawaii and Japan down to Australia through the Indian Ocean to the east coast of Africa. All stages of fringing reefs, barrier reefs, and atolls are exhibited, but barrier reefs and atolls are the most common. Reef formations are composed mostly of hard corals and often develop prominent algal ridges on the seaward margin of the reef crest. On the shore side of the reef crest, an extensive reef flat may form. Of the three regions, the Indo-Pacific is the most biodiverse. It is home to 700 coral species and over 3,000 coral reef fishes. This biodiversity may be due to the size of the region and the abundance of coastline suitable for coral reef growth or the relatively mild effects of the Pleistocene ice age which wiped out many species from the Caribbean seas.<ref name="william" /> | ||

[[File:greatercaribbean.gif|200px|left|image credit: William Alevizon]] | [[File:greatercaribbean.gif|200px|left|image credit: William Alevizon]] '''Greater Caribbean''' | ||

'''Greater Caribbean''' | |||

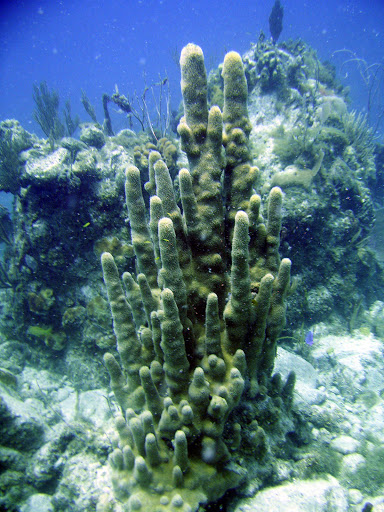

The Greater Caribbean covers the subtropics of the Atlantic Ocean as far north as Bermuda down to South America's northern coast. In comparison to the prolific Indo-Pacific, the Greater Caribbean only accounts for 8% of the world's corals. Most of these are in the form of fringing reefs. The very few barrier reefs and atolls that do exist were likely developed in ways other than volcanic island subsidence. Caribbean reefs are characterized by their diversity and abundance of sponges and octocorals, lack of a widely developed algal ridge, and frequent patch reefs. The reefs are home to 65 species of hard corals and 500-700 species of reef fishes. The relative low biodiversity in this region was caused by the harsh effects of the Pleistocene ice age; many species went extinct when the sea temperature and water level declined. Isolated from the Indo-Pacific (which did not experience the same harsh conditions in the ice age), these species were never reintroduced to the region. The health of reefs in the Greater Caribbean is currently of great concern to habitants and researchers. The reefs are very important to the surrounding populations; they protect the shore from hurricanes as well as fuel a huge fishing and tourism industry. But in recent years, recreational overuse, decline in water quality, and prevalence of disease have caused coral death and decreased growth. Stricter regulations and protection hope to help combat the decline. | The Greater Caribbean covers the subtropics of the Atlantic Ocean as far north as Bermuda down to South America's northern coast. In comparison to the prolific Indo-Pacific, the Greater Caribbean only accounts for 8% of the world's corals. Most of these are in the form of fringing reefs. The very few barrier reefs and atolls that do exist were likely developed in ways other than volcanic island subsidence. Caribbean reefs are characterized by their diversity and abundance of sponges and octocorals, lack of a widely developed algal ridge, and frequent patch reefs. The reefs are home to 65 species of hard corals and 500-700 species of reef fishes. The relative low biodiversity in this region was caused by the harsh effects of the Pleistocene ice age; many species went extinct when the sea temperature and water level declined. Isolated from the Indo-Pacific (which did not experience the same harsh conditions in the ice age), these species were never reintroduced to the region. The health of reefs in the Greater Caribbean is currently of great concern to habitants and researchers. The reefs are very important to the surrounding populations; they protect the shore from hurricanes as well as fuel a huge fishing and tourism industry. But in recent years, recreational overuse, decline in water quality, and prevalence of disease have caused coral death and decreased growth. Stricter regulations and protection hope to help combat the decline. | ||

Revision as of 18:59, 22 April 2013

Where are Coral Reefs Found?

Coral Reefs are typically found in a band stretching from 30° north to 30° south of the equator where the water temperature stays above 68°F year round. Because the coral relies on its photosynthesizing symbiote, zooanthellae, for food, growth occurs in areas of shallow depth and low turbidity where sunlight can reach the coral. Water movement is also important to the health of coral reefs. Tidal shifts and waves wash away waste and bring nutrients and oxygen to corals.[1]

Specific Environmental Conditions

- Temperature

- Corals grow best in the warmer waters of the subtropics where temperatures remain between 68-83°F. Coral productivity is highest when temperatures are around 74-78°F.[1]

- Depth

- Because corals are reliant on their symbiosis with photosynthetic algae, they are restricted to shallow, sunlight waters. Depth can range up to several hundred feet in rare occasions but is normally restricted to the top 30-100 ft of the euphotic zone. [1]

- Emersion

- Most corals will die if they are exposed to open air and sunlight, but some species may survive short periods of time out of the water during extremely low tides.[1]

- Salinity

- Corals grow in normal ocean salinity, ideally 35-38 ppt.[1] However, some corals have been known to grow in the extreme salinities of the Red Sea, of up to 40 ppt.

- Turbidity

- Sediments causing high turbidity threaten coral survival by blocking sunlight and suffocating polyps. Corals prefer clear water where they can effectively feed and continue building. [1]

- Bottom Topography

- Corals need a hard, stable substrate to anchor to. Cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) must bind sediments in muddy or sandy bottoms to form a tough, leathery mat before coral can grow. [1]

Coral Reef Distribution

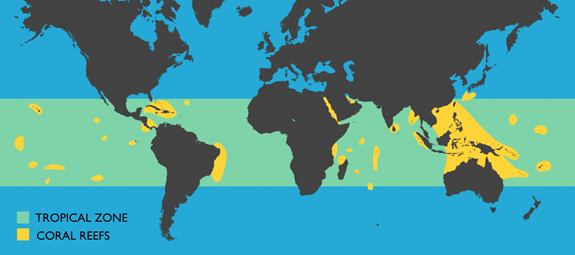

Because of the very specific circumstances required for coral reefs to form and flourish, it is not surprising that only 0.089% of the world's oceans are occupied by such formations. The majority of these reefs are confined to two geographic areas: the Caribbean and the Indo-Pacific, encompassing everything from the Red Sea to the Central Pacific. [2] The map below illustrates the distribution of coral reefs. Notice the relative absence of reef formations along the west coasts of the Americas and Africa. This is due to the upwelling of cold, nutrient rich water which discourages coral growth. [3]

Reefs by Region

The coral reefs in the world can be grouped into three isolated regions: the Indo-Pacific, the Greater Caribbean, and the Red Sea. The gene flow between these three regions has been close to cut off (the Red Sea is connected to the Indian Ocean only by the Bab el-Mandeb strait) resulting in the development of a significant proportion of endemic (only existing in one place) species and unique regional diversity.[3]

Indo-Pacific

The Indo-Pacific is the largest of the three regions, encompassing the central and south pacific ocean from Hawaii and Japan down to Australia through the Indian Ocean to the east coast of Africa. All stages of fringing reefs, barrier reefs, and atolls are exhibited, but barrier reefs and atolls are the most common. Reef formations are composed mostly of hard corals and often develop prominent algal ridges on the seaward margin of the reef crest. On the shore side of the reef crest, an extensive reef flat may form. Of the three regions, the Indo-Pacific is the most biodiverse. It is home to 700 coral species and over 3,000 coral reef fishes. This biodiversity may be due to the size of the region and the abundance of coastline suitable for coral reef growth or the relatively mild effects of the Pleistocene ice age which wiped out many species from the Caribbean seas.[3]

Greater Caribbean

The Greater Caribbean covers the subtropics of the Atlantic Ocean as far north as Bermuda down to South America's northern coast. In comparison to the prolific Indo-Pacific, the Greater Caribbean only accounts for 8% of the world's corals. Most of these are in the form of fringing reefs. The very few barrier reefs and atolls that do exist were likely developed in ways other than volcanic island subsidence. Caribbean reefs are characterized by their diversity and abundance of sponges and octocorals, lack of a widely developed algal ridge, and frequent patch reefs. The reefs are home to 65 species of hard corals and 500-700 species of reef fishes. The relative low biodiversity in this region was caused by the harsh effects of the Pleistocene ice age; many species went extinct when the sea temperature and water level declined. Isolated from the Indo-Pacific (which did not experience the same harsh conditions in the ice age), these species were never reintroduced to the region. The health of reefs in the Greater Caribbean is currently of great concern to habitants and researchers. The reefs are very important to the surrounding populations; they protect the shore from hurricanes as well as fuel a huge fishing and tourism industry. But in recent years, recreational overuse, decline in water quality, and prevalence of disease have caused coral death and decreased growth. Stricter regulations and protection hope to help combat the decline.

Red Sea

The Red Sea is the smallest region, a narrow strip of water between Africa and the Middle East, joined to the Indian Ocean by the Bab el-Mandeb strait. Compared to the other regions, the conditions of the Red Sea are much harsher. Relatively shallow and surrounding by very dry climates, the water temperature and salinity are much higher than is normally tolerated by corals. That said, the Red Sea exhibits amazing biodiversity with more than 1,200 species of reef fishes and 300 species of coral, significantly higher than in the whole Greater Caribbean. Reef formations in the Red Sea are primarily fringing reefs directly off the coasts with small lagoons supporting seagrass meadows, mangroves, or patch reefs. There are some unusual reef formations that cannot be classified by the conventional categories and are likely the result of the active tectonic forces in the area. A deep, narrow trench known as the Rift Valley runs down the center of the Red Sea, currently widening as the African and Arabian continents drift apart. Corals in the Red Sea are generally considered healthy. They exhibit minimal coral bleaching and disease, although researchers worry about developing regions and the prevalence of diving expeditions which may threaten coral health in the future.