Cyclones: Difference between revisions

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

<span class="floatright" style="height:288px; width:214;">http://www.japanfocus.org/data/mechanism-of-tropical-cyclone.jpg</span> | <span class="floatright" style="height:288px; width:214;">http://www.japanfocus.org/data/mechanism-of-tropical-cyclone.jpg</span> | ||

<br clear=all>===What Kind of Damage does it do to coral reefs?=== | <br clear=all> | ||

===What Kind of Damage does it do to coral reefs?=== | |||

Reef damage varies with the intensity, distance, and location of a cyclone. With the right conditions, a cyclone can be catastrophic to a coral community and its inhabitants. | Reef damage varies with the intensity, distance, and location of a cyclone. With the right conditions, a cyclone can be catastrophic to a coral community and its inhabitants. | ||

Revision as of 15:19, 17 April 2013

Tropical Cyclones

What is a tropical cyclone?

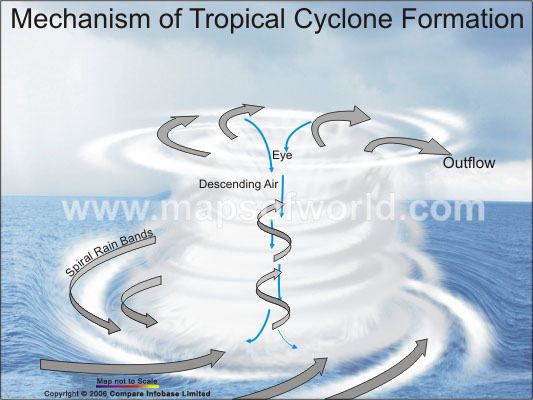

Tropical cyclones are intense cells of low pressure accompanied by circular winds, thunderstorms, and heavy rain. They contain a central eye. The steep pressure gradient between the storm and surrounding air creates damaging storm surges of 2-5 m above the predicted level. The storm surge is located on the left of the storm in the southern hemisphere because winds spin in the clockwise direction and to the right in the northern hemisphere because winds circulate in the counterclockwise direction. The pathway of a cyclone is unpredictable, and it can make instantaneous switches. Cyclones can create waves up to 8-10 m depending on its wind strength. [1] A tropical cyclone starts out as a tropical depression and becomes a tropical storm as it gains strength. It finally graduates to become a cyclone when winds reach a speed of 34 m/s. Depending on the location of the storm, a cyclone has different names: in the North Atlantic or North-Eastern Pacific Oceans, it is referred to as a hurricane; in the Western Pacific region, it is called a typhoon; and in the Southern Hemisphere and Indian Ocean, it is known as a cyclone.[2] Tropical cyclones usually cause lots of damage to coastal communities, infrastructure, and ecosystems. In many coral reefs, tropical cyclones are the main damaging force. It influences coral cover, species diversity, and reef productivity. Strong cyclones have the ability to shape the coral reef by affecting the benthic reef communities and underlying reef structure. Fortunately, coral reefs have a certain physical resilience against damaging cyclones. Therefore, they can recover relatively quickly and easily if there is not a lot of outside stresses. This is why it is important to make sure we, as humans, keep the coral reefs as strong as possible. [3]

What Kind of Damage does it do to coral reefs?

Reef damage varies with the intensity, distance, and location of a cyclone. With the right conditions, a cyclone can be catastrophic to a coral community and its inhabitants.

Effects on Water

The sedimentary processes, salinity levels, and sea levels of a coral reef are altered from cyclones. This can damage the coral reef because they are so sensitive to their surroundings and any changes in them. Increased turbidity, as a result of cyclonic winds, causes more sediment particles and material to be dispersed within coral reefs. This material can negatively affect the growth of coral and even kill it by decreasing the permeability of light to coral, which is necessary for photosynthetic processes. Mud sedimentation decreases shelter availability for other organisms residing in coral reefs. Salinity levels decrease in ocean water due to increased water fall. Corals will bleach from the resulting stress on water pH. Finally, sea levels will also decrease with the low pressure generated by cyclones. This leaves some corals, that are usually submerged at specific sea levels, exposed. When sea levels are too high, light will not be able to reach the coral, which is essential for the coral to absorb nutrients and energy.[4]

Erosion

Increased amounts of broken coral, sediments, and other organisms are displaced due to stronger wave currents, which results in some areas of the reef being buried in sediment while others are left bare. At the same time, storm surges will uplift these materials and push them up to the shore into features known as storm ridges, the result of severe tropical cyclones. These are detrimental to atoll reefs because storm ridges have the potential to block off lagoons and induce deterioration of water quality. Stronger storm surges are needed to break off pieces of larger colonies. The breakage of coral reef depends on the location, shape, and strength of the coral itself: branching corals are recorded as being most affected, compared to colonies such as brain or boulder coral. This is because these massive colonies are more stable and create the foundational layer of coral reefs. The strength of coral can be further weakened by parasitic organisms and disease.[5]

Effects on Biodiversity

Cyclones effect species richness, distribution, and behavior. Most tropical cyclones do not directly kill reef fish. Reef fish are usually killed through the disruptions of their surroundings as discussed above. However, these mortalities are not selective, which means any number of species can be affected. This can be catastrophic if keystone and other important species are wiped out. Cyclones influence juvenile fish the most in shallow waters. When the density and distribution of these juvenile fish is disrupted, it negatively impacts the future species richness of the coral reef. The destruction of a coral reef is usually followed by a change in trophic levels of the fish community. Other reef species such as algae, sponges, and echinoderms are reduced in density, especially in shallow waters. Algae and sponges can be uprooted and displaced onshore due to strong winds and storm surges. [6]

Recovery

Tropical cyclones cause so much damage, and unfortunately, coral reefs take a long period of time to recover. Greater damage can take anywhere between 5 to 40 years to recover.[7] Favorable conditions for growth also have to be present for the coral reef to recover. A coral reef needs many things. Salinity and sea levels need to return back to normal. The reef should be connected to an outside sources, such as other healthy reefs, so that organisms and larvae can travel to reseed the damaged community. Without an outsource of larvae, a coral reef will take much longer to regrow. The regrowth of coral fragments is necessary to repopulate the coral gardens. The regeneration of partially damaged coral colonies help reestablish old colonies of coral. The presence of human stresses should be nonexistent, or minimal at most. Coral reefs that are unaffected by outside stresses have been known to recover from tropical cyclones quicker. Coral reefs were built to withstand the physical damage of natural disasters like tropical cyclones. However, the structures are weakened by outside stresses such as changing pH, salinity, and nutrient levels. If the coral reef was originally healthy before a tropical cyclone, it has a better chance of fully recovering.[8]

Impacts on the Great Barrier Reef

Case Study: Cyclone Ingrid

Tropical Cyclone Ingrid hit the Great Barrier Reef in March of 2005. Ingrid ranged between a category 3 and category 5 cyclone with winds up to 250 km/s; however, the actual size of the cyclone was small. The core of the cyclone was only 10-15 km diameter. The winds caused waves of up to 15 m in the open ocean and around 5 m in the Great Barrier Reef. The extent of the damage was caused by the fact that Ingrid hit three different states in Australia.[9] This is the first time in history that a tropical cyclone hit this many states in Australia. The intensity of the damage was caused by the high winds in such a small area. The offshore reef had the deepest depth of damage, but the inshore reefs had the most coral reef and dislodgement. Areas with less than 25 m/s winds suffered minimal damage, while areas with greater than 33 m/s winds encountered cataclysmic damage. In the worst affected areas, hard coral cover decreased 8oo%. The biodiversity decreased 250% and amount of coral recruits decreased by about 30%.[10]

Case study: Cyclone Yasi

Tropical Cyclone Yasi made landfall in Queensland, Australia in February of 2011. Yasi reached a category 5 cyclone with strong, damaging winds of 285 km/s. Reefs near the eye of the storm suffered the most damage, and the reefs south of the eye suffered more than the reefs to the north of the eye. Specifically, the 61 coral gardens that were around the peak winds were damaged the most. Out of these 58 reefs suffered destruction to the living communities, and 47 of the reefs suffered from structural damage. Shelf position also affected the extent of damage to the coral: outer reefs experienced more devastation than mid-shelf reefs.[11] Some coral gardens around the Queensland area were reduced to rubble. Many coral heads, known as "bommies" in the area, were found lying on the ocean bed far away from where they were supposed to be. Because of these reasons, the damage was patchy, so some neighboring coral gardens remaining intact. These nearby corals can help facilitate the regrowth of the damaged coral gardens.[12] Cyclone Yasi's physical destruction ranged from minor tissue injuries on the edges of some coral colonies to complete removal of all sessile organisms. Fragile, fast-growing corals such as branching and plating corals endured the most damage, while more durable, slow-growing coral such as encrusting and brain coral suffered relatively less damage.[13] Yasi's damage to the coral gardens have already caused the coral trout to go extinct.[14] It is possible that Yasi may have caused more damage than any other storm since early 1900s.[15] The extent of the damage could take anywhere between 10 to 20 years to restore good coral cover; however, some coral could take longer than that to fully recover. Months before Yasi, several floods swept through the same area, carrying sediment and pesticides back out into the ocean. This was compounded by the high tides caused by the cyclone. These pesticides and sediments could be potentially damaging to already fragile coral, causing latent death. Fortunately for people in the area, Queensland is not a popular reef site; therefore, there was not a severe impact to the tourism industry.[16]

Notes

- ↑ Harmelin-Vivien, Mireille L. "The Effects of Storms and Cyclones on Coral Reefs: A Review." Journal of Coastal Research (1994): 211-31. JSTOR. Coastal Education & Research Foundation, Inc. Web. 26 Feb. 2013.

- ↑ "TCFAQ A1) What Is a Hurricane, Typhoon, or Tropical Cyclone?" Atlantic Oceanographic & Meteorological Laboratory: National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration. Hurricane Research Division, 15 July 2011. Web. 5 Apr. 2013.

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority 2011, Impacts of tropical cyclone Yasi on the Great Barrier Reef: a report on the findings of a rapid ecological impact assessment, July 2011, GBRMPA, Townsville.

- ↑ Scoffin, T.P. "The Geological Effects of Hurricanes on Coral Reefs and the Interpretation of Storm Deposits - Springer." Coral Reefs 12.3-4 (1993): 203-21. Springer Link. Springer-Verlag, 01 Nov. 1993. Web. 26 Feb. 2013.

- ↑ Scoffin, T.P. "The Geological Effects of Hurricanes on Coral Reefs and the Interpretation of Storm Deposits - Springer." Coral Reefs 12.3-4 (1993): 203-21. Springer Link. Springer-Verlag, 01 Nov. 1993. Web. 26 Feb. 2013.

- ↑ Harmelin-Vivien, Mireille L. "The Effects of Storms and Cyclones on Coral Reefs: A Review." Journal of Coastal Research (1994): 211-31. JSTOR. Coastal Education & Research Foundation, Inc. Web. 26 Feb. 2013.

- ↑ Hughes, T.P., A.H. Baird, D.R. Bellwood, M. Card, S.R. Connolly, C. Folke, R. Grosberg, O. Hoegh-Guldberg, J.B.C. Jackson, J. Kleypas, J.M. Lough, P. Marshall, M. Nystrom, S.R. Palumbi, J.M. Pandolfi, B. Rosen, and J. Roughgarden. "Climate Change, Human Impacts, and the Resilience of Coral Reefs." Science 301.5635 (2003): 929-33. Science Magazine. 15 Aug. 2003. Web. 26 Feb. 2013.

- ↑ "Recovery From Bleaching." Coral Reefs: Recovery from Bleaching. The Nature Conservatory, 2007. Web. 5 Apr. 2013.

- ↑ "Severe Tropical Cyclone Ingrid." Australian Government: Bureau of Meteorology. Commonwealth of Australia, n.d. Web. 5 Apr. 2013.

- ↑ Fabricius, Katharina E., Glenn De'ath, Marji Lee Puotinen, Terry Done, Timothy F. Cooper, and Scott C Burgess. "Disturbance Gradients on Inshore and Offshore Coral Reefs Caused by a Severe Tropical Cyclone." Diss. N.d. Abstract. Association for the Sciences of Limnology and Oceanography. N.p., 2010. Web. 26 Feb. 2013.

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority 2011, Impacts of tropical cyclone Yasi on the Great Barrier Reef: a report on the findings of a rapid ecological impact assessment, July 2011, GBRMPA, Townsville.

- ↑ "ABC Rural." Long-term Coral Damage from Cyclone Yasi. ABC, 22 Mar. 2011. Web. 26 Feb. 2013.

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority 2011, Impacts of tropical cyclone Yasi on the Great Barrier Reef: a report on the findings of a rapid ecological impact assessment, July 2011, GBRMPA, Townsville.

- ↑ "ABC Rural." Long-term Coral Damage from Cyclone Yasi. ABC, 22 Mar. 2011. Web. 26 Feb. 2013.

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority 2011, Impacts of tropical cyclone Yasi on the Great Barrier Reef: a report on the findings of a rapid ecological impact assessment, July 2011, GBRMPA, Townsville.

- ↑ "ABC Rural." Long-term Coral Damage from Cyclone Yasi. ABC, 22 Mar. 2011. Web. 26 Feb. 2013.